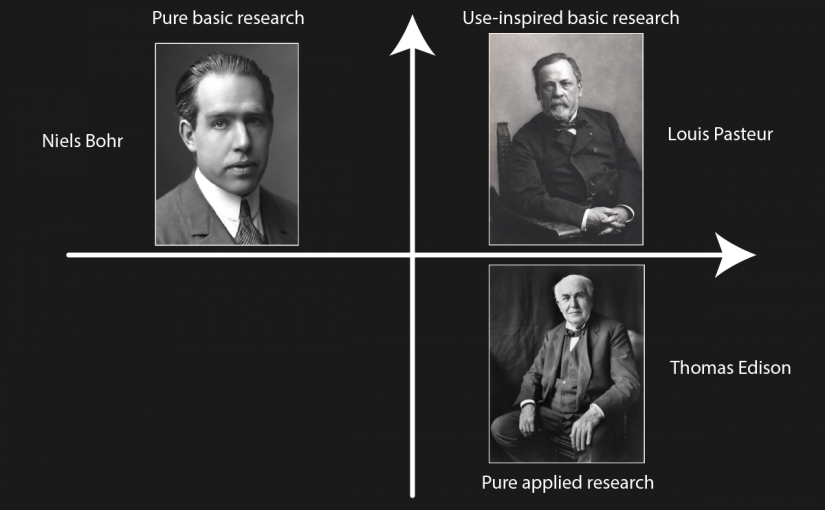

Earlier this year, at a Gordon conference, I listened to a talk by Prof. George Whitesides on soft robotics. In his introduction, he talked about Pasteur’s quadrant. The idea is that one can categorize research works into four quadrants: one axis is the scale of immediate usefulness, and the other axis is the scale of fundamental understanding. On this chart, Thomas Edison’s work is high on immediate usefulness but low on fundamental understanding, whereas Niels Bohr’s work is high on fundamental understanding but low on immediate usefulness. Pasteur’s work is considered high on both scales. Many of R1 university research, Prof. Whitesides pointed out, lie in the empty 3rd quadrant. He urged the young people in the audience to do research in Pasteur’s quadrant.

In a slightly more relaxed setting, he has said similar things. He advised scientists who just began their careers to consider selecting topics that other people care about, “like death” (overheard, no exaggeration). The question of “who cares” needs justification other than the researcher’s own curiosity.

I jotted down a list of research topics that interest me: morphogenesis and pattern formation, 3D printing, the origin of life, artificial intelligence, water, and energy. Each will be examined in due course.