Another academic year, four more courses. This year, I audited Fluid Dynamics by Mahadevan, and Frontier in Biophysics by Sunney Xie in the fall, and Thermophysics by Girma Hailu and Physical Mathematics II by Eli Tziperman in the spring. Every one of them is a rewarding experience.

Another academic year, four more courses. This year, I audited Fluid Dynamics by Mahadevan, and Frontier in Biophysics by Sunney Xie in the fall, and Thermophysics by Girma Hailu and Physical Mathematics II by Eli Tziperman in the spring. Every one of them is a rewarding experience.

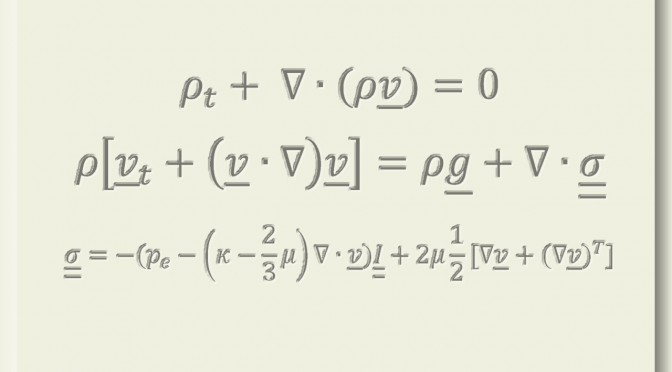

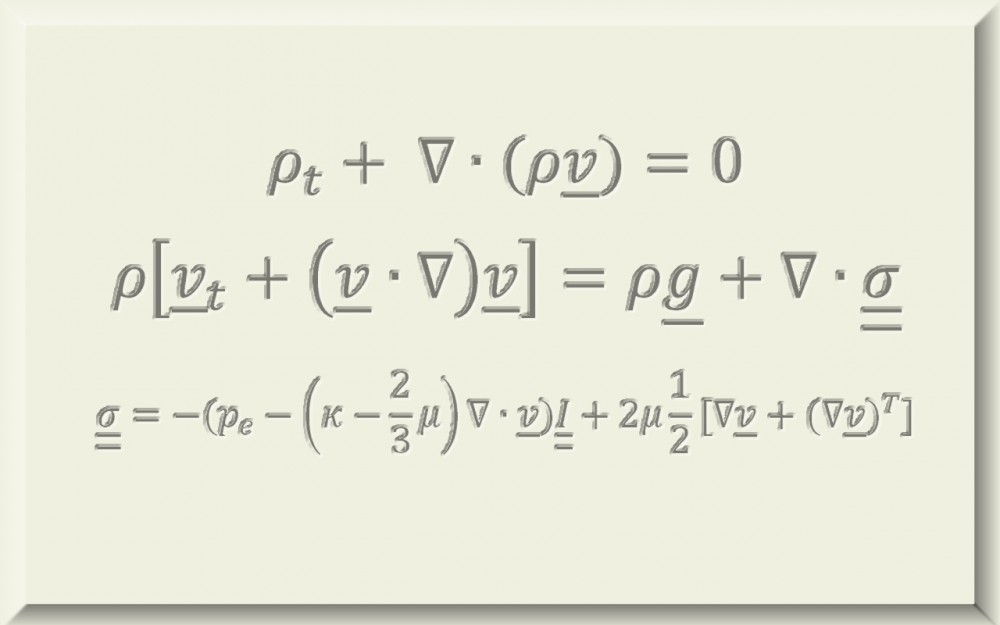

This is the second time I audited Maha’s fluid dynamics class. A year and half ago, when I first sat in Maha’s class, I was playing catch-up on required maths all the time. By the time he reached the full form of Navier-Stokes equation, which was about six weeks into the semester, my mind was already stuffed and could not take in any more. This time around, the situation got much better. In addition, I had a study buddy with whom I discussed homework problems, and the discussion helped understanding enormously.

Maha covered a wide range of topics in the class: dimensional analysis, kinematics, derivation of Navier-Stokes equations, Stokes’ flows, lubrication theory, surface tension, waves, instability, and boundary layer theory. The textbook he uses is Elementary Fluid Dynamics by D.J. Acheson, although he often digresses in lectures. The class emphasizes intuitive understanding, and Maha often uses dimensional analysis to guide the intuition before any formal analysis.

One quote he likes to repeat is “All models are wrong, but some are useful”. It is by George Box, a statistician. Being a fervent quote collector, I looked it up. Pithy it sounds, it is not like those witty single standalone quotes; there is actually a book about it. One may gain some understanding about George Box’s idea on model-building on this wikiquote page. I quote a few to illustrate the key idea.

A mechanistic model has the following advantages:

1. It contributes to our scientific understanding of the phenomenon under study.

2. It usually provides a better basis for extrapolation (at least to conditions worthy of further experimental investigation if not through the entire range of all input variables).

3. It tends to be parsimonious (i.e, frugal) in the use of parameters and to provide better estimates of the responseRemember that all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful.

In fact, the longer one ponders these quotes, the wider one would find their applicability. Not just mechanical models, but all physical models are wrong, really. But we often confuse models with reality. The question “is light particle or wave?” is not just a false dilemma but a completely wrong question. The correctly phrased question is “should be light be modeled as particle or as wave?” As another example, the molecular description of all the reactions in organic and inorganic chemistry are based on molecular structures, which are in fact only models, albeit very good ones. They are much less quantitative than models of particles or waves, and much less powerful for use to predict or extrapolate than the models of lights. Still, they are useful within a certain extent.

In a way, the insight that “all models are wrong, but some are useful” is a liberating idea. It frees one from the constant worry of constructing a “wrong” model, and makes one bolder in attempting to build something useful.