Every major in college education has a standard set of courses that a student needs to take in order to get a degree. For example, a physics major needs to take classical mechanics, electrodynamics, statistical mechanics, and quantum mechanics; another example, a chemistry major needs to take inorganic, organic, physical, and analytical chemistry. Traditionally, these courses have been deemed a requirement for future jobs. Successful graduates will be able to call themselves physicists or chemists, or be identified as physicists or chemists by others. They serve as convenient labels in the job market and in their future careers.

But the reality of today’s workplace suggests that those labels seem almost meaningless. Perhaps the most revealing manifestation of this reality is in scientific and technological research. The research today is conducted at an industrial scale, with nations and corporations pouring resources into universities and research centers in the hope that the outcome of the research (which is the return of their investment) will boost the national and/or institutional competitiveness at a global scale. It has evolved and become quite different from the research, perhaps only a century ago, when researchers were those individuals who had the luxury and curiosity to explore how things work and why.

One important feature of the research at the industrial scale is the increasing degree of specialization: because a lot more has been made known in the world of science and technology, one person cannot know it all so one has to specialize in a particular area of research. This is where the preexisting labels, however convenient in the job market, get in the way. On the one hand, an individual might feel unwilling to proceed with a line of research because he/she is not specialized in whatever discipline the research is deemed belong to. On the other hand, one’s superiors might feel an individual unqualified for a particular area of research just because that individual is not trained as such or such. Both situations exemplify the failure to take into account the dynamic nature of an individual’s intellectual capacity, and perhaps, a failure to recognize that existing disciplines were themselves just labels of specializations a few decades ago, and they are not labels of individuals’ mental characteristics.

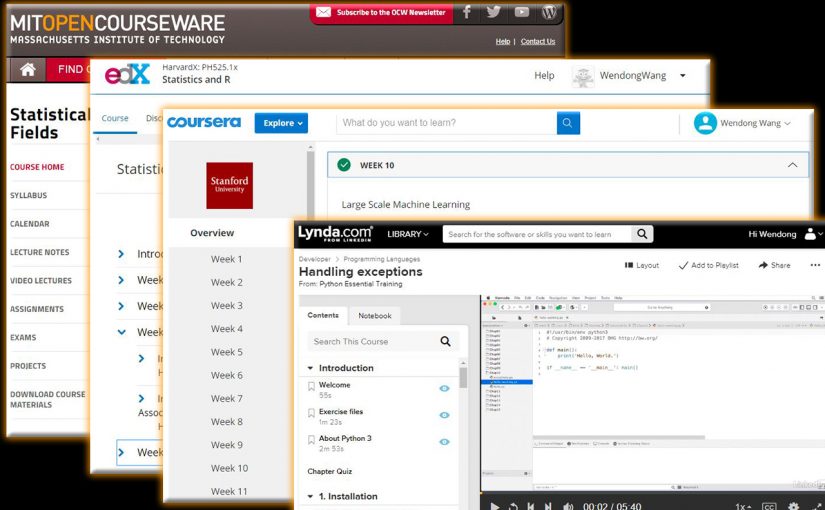

Now with the advent of online education, an individual can tailor one’s knowledge profile and skill set seemingly at will, so how should one choose? There could be a variety of opinions on this question: job market reality, future earnings, societal needs, and of course, one’s curiosity, individual gifts and talents, etc. I will venture to give my own, given the context set in this post, in the realm of research. I believe that a researcher should learn what is necessary in order to create something new.

Once getting into research, one quickly realizes that understanding at the textbook level, particularly undergraduate textbooks, are not enough. (Their idealized version of the development of concepts could even be misleading.) Moreover, the selection of topics to be included in and excluded from a particular textbook is often a personal and subjective judgment of the authors. In research, however, it is often said that nature doesn’t ask questions addressed to a specific discipline, and the answer is certainly not included in a specific textbook. A researcher ultimately bears the responsibility of making sure what he/she creates is something new, not just a slightly modified copy of something already existing. That responsibility necessitates familiarity with the existing literature in a given field. Given the interdisciplinary reality of today’s research, one’s existing education, however comprehensive, often has gaps that prevent a researcher from appreciating all the existing literature on a given subject. A responsible researcher should try to fill those gaps, and to fill those gaps is perhaps the best use of online courses for a researcher.